BY: Bob Montgomerie, Queen’s University | 4 December 2017

Last Wednesday, 29 November, was the 390th anniversary of the birth of John Wray, exactly one week later than the birthday of his student, friend, collaborator, and benefactor Francis Willughby (on 22 November) who was 7 years younger. Wray changed his surname to Ray when he was 43 years old having decided then that that was really the ancestral spelling. Ray and Willughby are not (yet) household names for students of ornithology, but they should be for they really founded the discipline in the English-speaking world during the late Renaissance of 17th century England.

Ray was the subject of a major biography by Charles Raven published in 1942, a book that has been called “one of the great works in the history of science” but that book is old enough that most ornithologists are not aware of it. Ray published books on birds, mammals, fishes, insects, and plants, and has a book publisher (The Ray Society), a natural scientists’ club at Cambridge (John Ray Society), and a science-Christian educational charity (John Ray Initiative) named in his honour. In contrast, Willughby, until recently, has achieved little more than a passing mention in many of the recent books on the history of ornithology.

Willughby and Ray met at Cambridge where Ray was Willughby’s tutor. There they developed a shared interest in natural history—Ray was particularly focused on plants while Willughby’s specialty was animals. At first Ray and Willughby went on excursions around southern Britain, spending some time on the west coast studying seabirds in 1662. Then, from 1663 to 1665, they travelled around continental Europe collecting specimens, illustrations, and information about plants and animals with the express purpose of taking a new approach to natural history (which they did in spades). They embarked on that expedition with Philip Skippon and Nathaniel Bacon and met many naturalists en route, including Martin Lister in Montpellier, France. Thus began a long history of young Cambridge and Oxford students undertaking natural history expeditions to interesting places, many of them later becoming noted ornithologists, including Julian Huxley, Niko Tinbergen, David Lack and Reynold Bray. Willughby and Ray also engaged in extensive correspondence with Skippon and Lister after their expedition, gathering more information for their books from them and other British naturalists. Nathaniel Bacon went to Virginia where he fomented revolution.

When they returned from their travels, Willughby, who was independently wealthy, provided the financial support so that he and Ray could devote full time to organizing their notes and collections with a look to publishing several books. Their goal was to publish comprehensive treatises on different taxa based on some of their new approaches to natural history: detailed descriptions of external features and internal anatomy, a focus on observation and analysis rather than rumour and hearsay, a listing of ‘characteristic marks’ that would help the reader distinguish one species from another, and illustrations of as many species as possible. They also broke from tradition by organizing taxa based on similarity of appearance and anatomy rather than solely on the organisms’ habitats or ways of life.

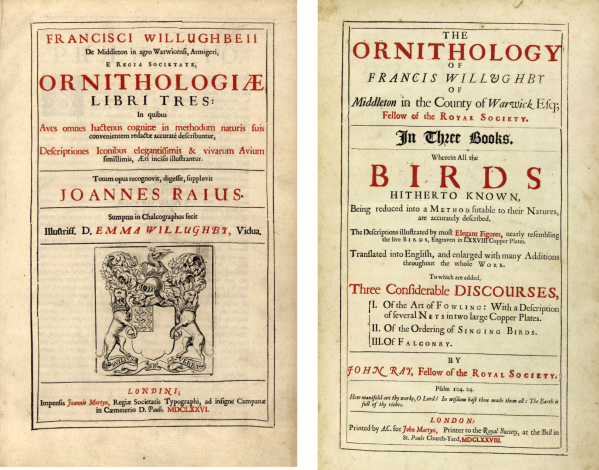

Willughby died of pleurisy at the age of 36, before they had finished a single volume, so Ray took up the task of bringing Willughby’s first volume—on birds— to print, based on Willughby’s extensive notes and drafts. This 489-page volume was published in Latin in 1676 with the title Francisci Willughbeii…Ornithologiae libri tres [The ornithology of Francis Willughby in three books], hereafter Ornithology [1]. The three ‘books’ in this single volume are: I. De Avibus in genere [Birds in General] on pages 1-23, II. De Avibus Majoribus [Land Birds] on pages 25-198 [2], and III. De Avibus Aquaticus [Aquatic Birds] on pages 199-295, followed by an Appendix, an index, and 77 black and white plates.

The Appendix in Ornithology is particularly notable because it describes ‘species’ for which they could obtain no evidence, explaining in detail their skepticism about the very existence of these birds:

Containing Such birds as we expect for fabulous, or such as are too briefly and inaccurately described to give us a full and sufficient knowledge of them, taken out of Franc. Hernandez especially. [3]

Willughby and Ray insisted on clear evidence before they would give credence to any species that they included in the main text of Ornithology. In fact they were wrong about many of the birds listed in that Appendix but good for them for being skeptical.

Two years later Ray published an English translation of Ornithology enhanced with some additional information sent to him by his correspondents, and large new sections on bird catching (fowling) and falconry. Those new sections mirrored the foundations of bird study in Europe where falconry and fowling—along with keeping songbirds in cages—were the primary connections that most people had with birds.

Anyone with an interest in birds should read Ray’s Willughby’s Ornithology. I marvel at the astuteness of the authors’ writing more than three centuries ago in an age when the first journals of science had just begun publication, and many people still thought that swallows overwintered in the mud, that the Harpy and the Phoenix were real, and that all birds had been created a few thousand years previously by an almighty deity. This volume and many of Ray’s 22 other books [4] are available for reading or download from the Biodiversity Heritage Library online.

Francis Willughby’s genius and contributions to ornithology (and Ornithology), and his myriad insights with respect to natural history, games, dictionaries and the study of language are highlighted in a new exhibition at the University of Sheffield (13 Nov 2017-28 Feb 2018; more information here), and in both an academic volume published in 2016 and a forthcoming trade book by Tim Birkhead. I will ask Tim to write a post about that new book when it comes out next spring.

Francis Willughby’s genius and contributions to ornithology (and Ornithology), and his myriad insights with respect to natural history, games, dictionaries and the study of language are highlighted in a new exhibition at the University of Sheffield (13 Nov 2017-28 Feb 2018; more information here), and in both an academic volume published in 2016 and a forthcoming trade book by Tim Birkhead. I will ask Tim to write a post about that new book when it comes out next spring.

I think that Ray and Willughby had an approach to natural history that is still valuable today: they went on expeditions with friends, they learned from and exchanged information with like-minded naturalists through voluminous correspondence, and they did not hesitate to think outside the box. With Twitter, Instagram and Messaging dominating our interactions these days, we sometimes forget about the value of corresponding with our colleagues even in the few sentences of enquiry or enlightenment that can be encompassed in a short email. 🙂

SOURCES

- Birkhead TR, editor (2016) Virtuoso by Nature: the Scientific Worlds of Francis Willughby FRS (1635-1672). Leiden: Brill.

- Egerton FN (2003) A history of the ecological sciences, Part 18: John Ray and his associates Francis Willughby and William Derham. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 86:301–313 <PDF available here>

- Raius J (1676) Francisci Willughbeii de Middleton in agro Warwicensi, Armigeri, e Regia Societate, Ornithologiae Libri Tres: in quibus Aves omnes hactenus cognitae in methodum naturis suis convenientem redactae accuratè describuntur, descriptiones iconibus elegantissimis & vivarum Avium simillimis, Aeri incisis illustrantur. London: John Martyn. <read at Google Books here>

- Ray J (1678) The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the county of Warwick Esq; Fellow of the Royal Society. In three books. Wherein all the birds hitherto known, being reduced into a method sutable [sic] to their natures, are accurately described. The descriptions illustrated by most elegant figures, nearly resembling the live birds, engraven in LXXVIII copper plates. Translated Into English, and enlarged with many additions throughout the whole work: To which are added, three considerable discourses, I. Of the art of fowling: with a description of several nets in two large copper plates. II. Of the ordering of Singing Birds. III. Of falconry. London: John Martyn. <read or download at BDHL here>

- Ray J (1713) Synopsis methodica avium & piscium: opus posthumum. vol. 1: Avium vol. 2: Piscium. [Synopsis of birds and fishes]. London: William Innys. <read or download at BDHL here>

Footnotes

- The full titles are given in the reference sources above and give a better picture of what this book is about and how Ray credited Willughby with the basis for the book.

- The English titles of these sections are from Ray’s translation of 1678

- Quotation from Ray 1678:385 where it is appears as the subtitle to the Appendix.

- Ray published several books on plants that were largely based on his own collections and investigations and provided what is considered to be the first definition of a biological species concept. He published one more book on birds, posthumously in 1713, in Latin, but I cannot (yet) tell whether that book was his own work done since Ornithology or a compilation of further notes and observations from Willughby’s legacy.

IMAGES: all images from Ornithology are in the public domain, copied from Biodiversity Heritage Library or Google Books online. Exhibition poster courtesy Amanda Bernstein, Rare Books Librarian, University of Sheffield.

One thought on “Ray of Light”